From the manipulation of the objects to its dematerialization

Alberto A. Abreu

Historian / Writer

The Baroque aesthetic tratadística (ensemble of treaties related to specific cultural ambient or a specific period in Portugal) defined the corresponding classicism in the light of two paradigms - those of Aristotle and Horace. The first recovered the Artwork’s project as mimesis (μιμησιζ). From the second he applied the motto “ut pictura poesis.”

Painting and poetry had the function to imitate (μιμέομαι, in medium voice) nature. And the painting appeared as mute poetry and poetry as spoken painting.

What nature concerns the scholastic had already produced distinction between “natura naturata” and “natura naturans.” Therefore, in this order of ideas, the mimesis would relate as much as reproducing nature objectively, as nature is to me is as well for the artist. The ideal of the true artist would be found in Zêuxis who painted grapes in such a realistic way that the birds would be fooled by it and would try to peck at them, as Apelles who put to debate the painting of a human figure in order to be criticized by each one of the analysts (but from his point of view: the shoemaker as a shoemaker and the poet as a poet).

Virgilio is a poet when he plays the sound and the ample movement of the waves¹, as well as when he deplores the ruin of Troy², to name just three celebrated verses. In fact, Plato had already drawn attention to the fact that poets, in ecstasy that a δαίμωυ interior drove them, trying to get closer, and then reproduce the perfect ideas from which the Renaissance identified their poetic objects. That’s why Camões says about the idealized woman ("that beautiful and pure semi-idea") which “is in thought as an idea”.

This reference to the Baroque aesthetic, as well to the Greek-Roman aesthetic, in no way comes inappropriately, even if it contradicts the followers, when we pretend to think the surrealism mouvement. It was one of the aesthetic currents (artistic and poetic) more passionately followed, more permanently maintained, but probably one of the most equivocally explained. Like the baroque painters, the surrealists are fundamentally poets. The objects, the elements, the fragments, the colors, the perspectives by them described or represented are susceptible to a semiology many times being poesis picta ou pictura poetica. A surrealist picture, even the one of a cadaver exquis is susceptible to a verbal “translation”. On the other hand, in a surrealist picture who appears is the painter himself, a true natura naturans of the real objects transformed in painted objects. In fact, what the painter represents from himself are the dreams witch express, in a psychoanalytic vision, what is above the reality where we find the super ego, the ideals, that in a nietzschean perspective, the social norms have prohibited and in a freudian perspective have castrated. The surrealism represents a oneiric construct and not the subconscious: “surrealism” is the transliteration of the French “surrealism”, that never pretended being “sub-” but actually “sur-realisme”.

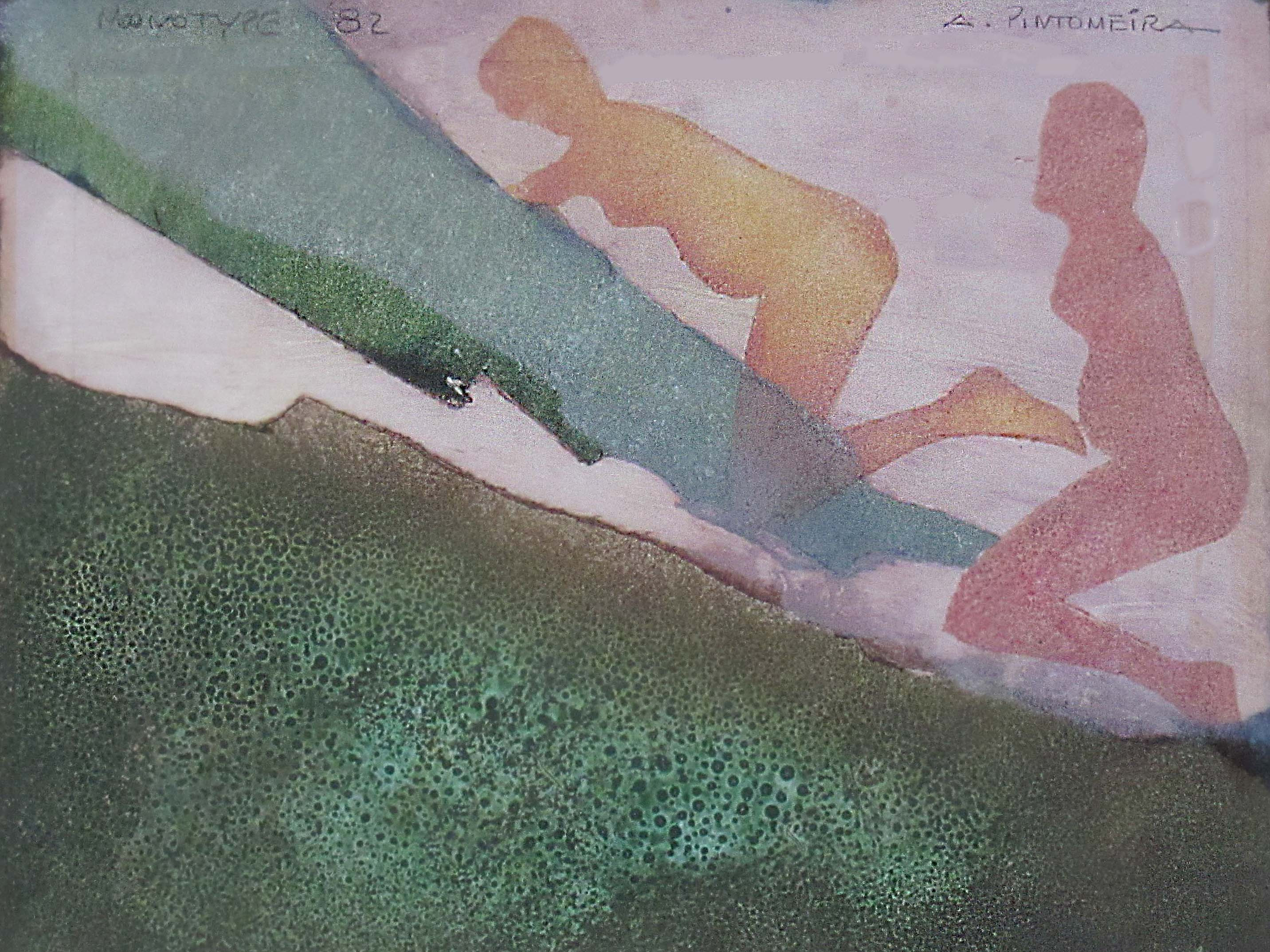

Therefore, the surrealism was one of the more lasting if not the more recurrent movements ever: we find relations more or less oneiric and “sur-real” in Bosh, in Arcimboldi, Goya, Klee. Linked to the COBRA Group, Pintomeira began by mimesis poetic surrealistic witch he developed during the years 70-79, constructing ruins, turgid shapes without visage, idealised bodies, perspectives, urban fantasy landscapes, some icons and objects resumed in a mystic recent phase and in a coeval of “immortalization” of the objects. These paintings, however, if the artist wants that the message reaches those who contemplate it, they can not suffer from any dysfunctions and, therefore, they are absolutely classic in its shape. Only the artist who dominates masterfully the technics and the materials, the outlines and the perspective, the color, the light and the shadow is able to paint surrealistically, like did Magritte, Dali, Cherico ou António Dacosta.

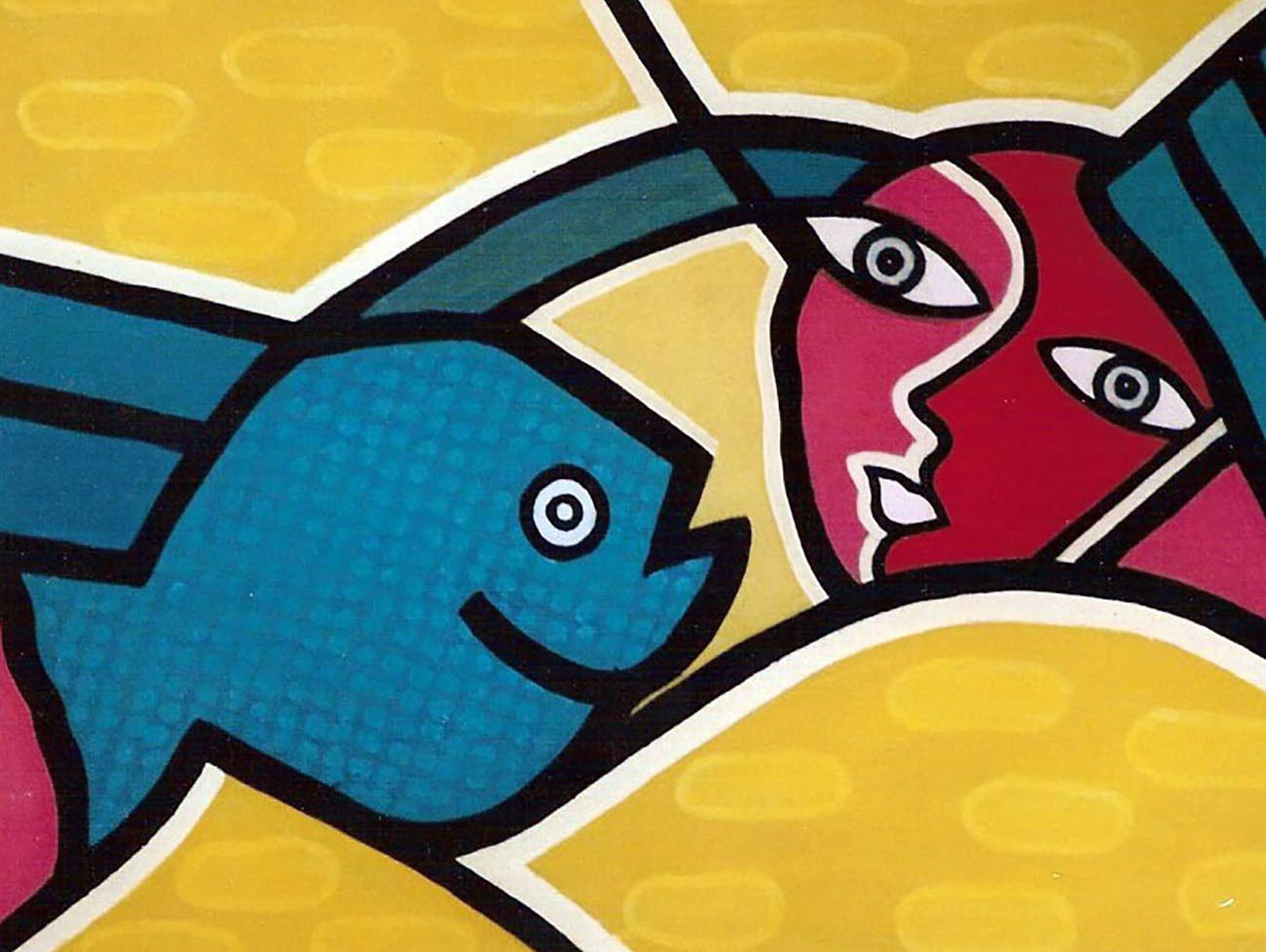

In fact, Pintomeira has always been very meticulous when representing the objects witch he choses to display in his paintings. The accentuation of an aspect of the beings – the face, the apple’s innards cut with a knife, allows us to discover a poetic-pictorial dimension into the veiled carapace. The intimacy one is looking to conquer or is dreaming about make of the contour a kind of shell that protect ourselves, looking like the maternal womb where we were happy and where we felt safe. The contour realizes, in the Pintomeira’s imaginary, the maternal uterus where we were formed, but also the first life’s conquest that was the cellular membrane. In fact, in the Contournism (outline style) of this artist, rarely the frame serves as a wrapper. On the contrary, the limits of the frame represent a pictogram, sometimes a sudden break as does a framed landscape, but of a universe where each of all beings appears incommunicable within the respective carapace. The painting appears, as a portrait of reality (dreamed or imagined, for all intents and purposes, created) the mimesis of a reality’s portion (natura-interi-or-naturata), not of natura naturans, because, at this stage, Pintomeira has not yet entered the transcendental domains.

Restless artist (and prolific), Pintomeira was always trying various experiences since its richer phase that was the "surrealism". We already pointed out the outlines, some icons and emblematic objects and religious symbols. He resumed some iconic solutions of the first phase and with them gave wide access at what he classified as "Mystique and mythology". But, in a painting where the lyricism appeared as virtually absent, it seems like, in this episode (at least what I figured) out of the artistic career of Pintomeira, are allegories of love. This is glossed by the classic myths of Leda and the Swan, being Leda as an ideal and soulless body (look oriented 150° in relation to the axis of the painting), the phallic Swan, engaging and protector, of white luciferin wings; and of Apollo and Daphne with this one fleeing towards the space in a 30° oblique angle. The mystical approach pulls out of the representation, no longer from veiled love, but from loving transgression in the Jewish myth of Adam's sin, but appearing to us disguised as a Faun fascinated before a female torso. The mystical itself and therefore also topically feminine, in the form of a "Mater dolorosa" looking at a 30° angle inside of herself, to the gentle pain passing through her mind.

In the Pintomeira encounter with the exterior nature, we observe a pictorial obsession about the calm horizontality of the Dutch landscape, with the geometric green of the fields separated by a luminous band on the horizon coming from the blue sky witch is getting denser as it rises up through the picture.

In this artworks of Pintomeira, who certainly observed attentively the Dutch zoographic tradition, wath we see is not the soft and the plane geometrics neither the chromatics of Mondrian, but the concave composition of the primitive paintings.

However, in a Ponte de Lima painting the composition is convex, the color grenat is dominant and the sun, the mountains, the bridge, the clothes drying, appear detached by a white contour witch transforms them into autonomous objects.

The objects get from Pintomeira a plastic dimension. Heirs from the 18th and 19th century “natures mortes,” as well as the baroque “bodegones”, in the oeuvre of Pintomeira they materialize themselves into authoritative figures, giving off other patterns, colors, dematerialised numerical series living almost as pure shapes in a platonic replacement of a universe of ideal figures.

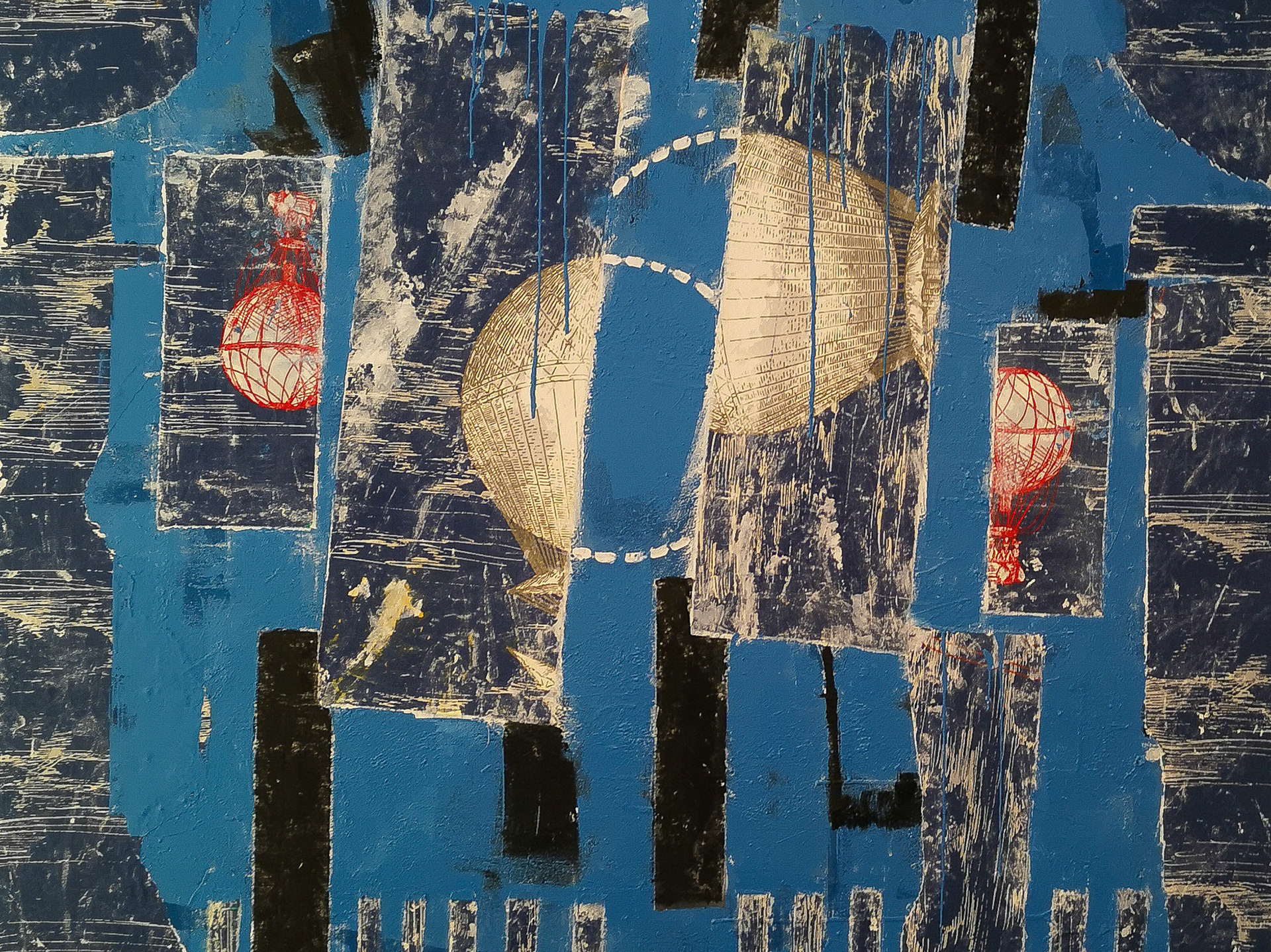

The objects dematerialization was the path followed by Pintomeira in a new line where the contour ended up reduced to a fillet, the objects’ images appear stylized when not reduced to colourless silhouettes nor respecting the other objects of the frame, and it is this compound of textures to give it pace, unreality, and a status of "pure forms". In this environment Pintomeira put quadrangular grids, birds, feminine silhouettes, faces, fruits, balconies, moons, and faces with amazed eyes. At the same time, the artist has rediscovered the plastic value of the primitive straightforwardness, the flat colors that came from Japan scaring away the symbolists and the "Nabis", of the ingenuous trace next to the pictorial construct more Raphaelesque, of the images overlay creating through colour intersectional objects. It is the own “métier” of painting that reveals exposing themes, forms of treatment, after denuding the style and dematerializing the objects.

In this retrospective we note the diachronic artistic evolution, but also the recurrence, despite it, of constant themes and topics, fundamentally a struggle for expression as such, through a serenity and security, resulting in a painting without anguish, fully made of a worldview constructed from a privileged lookout, located really on this side of the things and something beyond the problems.

¹ En 1,86: et uastos as litŏra fluctus

² En 2,361-362 : Quis clǎdem ilius noctis, quis funĕra fando / explicet aut possit lacrimis aequare labores?