LANDSCAPE

1987

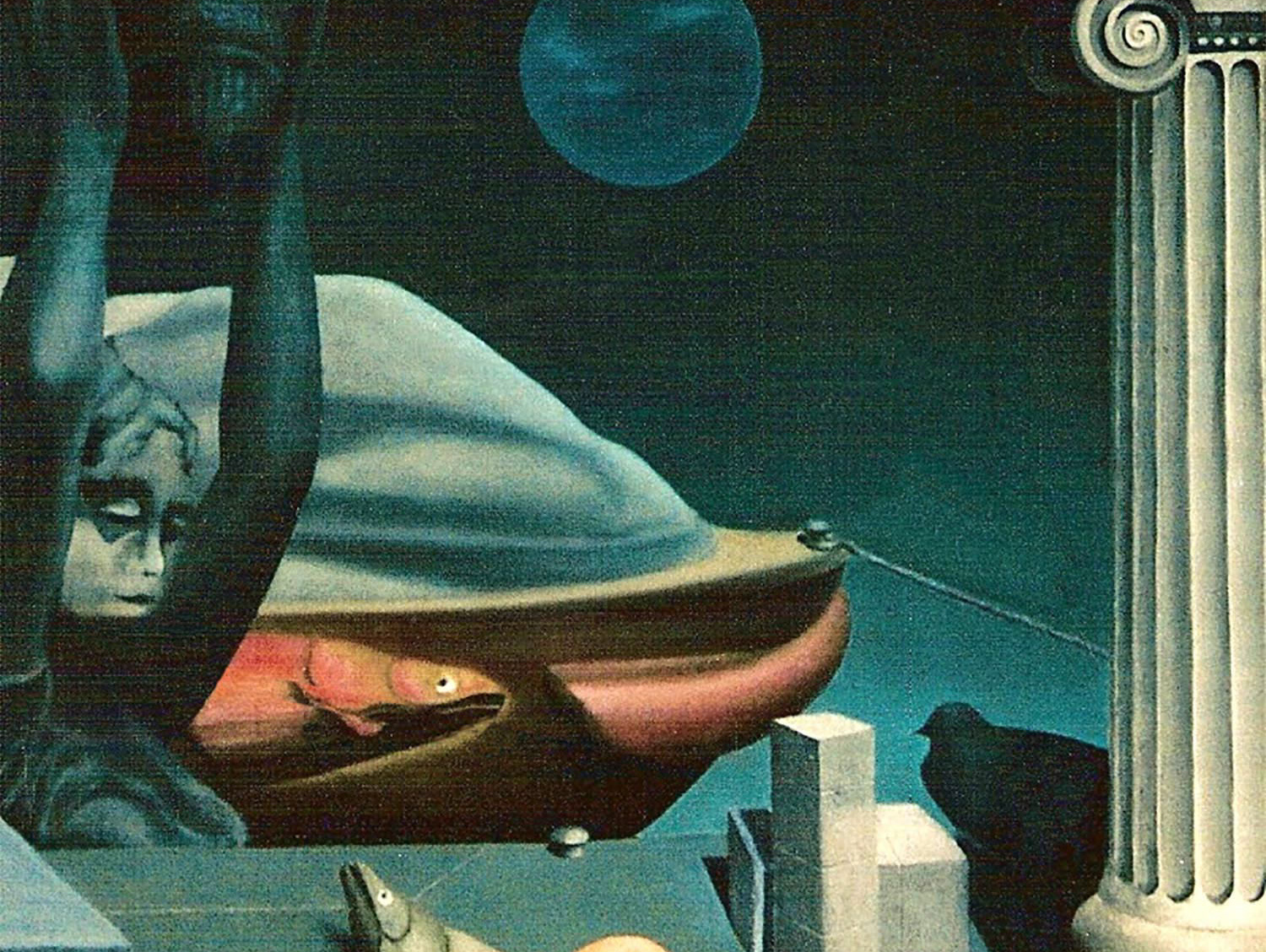

The composition presents itself as minimalist, without the elements that, normally, we find in a landscape: trees, rivers, people, animals, etc. This was the main line with which he structured most of his landscape works, existing a few, where we can see elements such as some tree trunks, meaning vertical geometric lines, but never eliminating the concept that was formerly determined: the strong apprehension of color, space and depth.

Pintomeira realized his meeting with the nature, offering to us this artistic expression about the landscape genre that, having never been his artistic expression area, far from it, he considered, at that time, an inevitability to bringing it to his Studio, where he worked it, following his own signature and aesthetical conception.

Alentejo | oil on canvas | 110x125x2cm | 1988 | Institutional Art Collection

Alentejo | oil on canvas | 100x125x2cm | 1987 | Institutional Art Collection

Alentejo | oil on canvas | 95x120x2cm | 1988 | Private Collection

Alentejo | oil on canvas | 110x125x2cm | 1988 | Private Collection

Ribatejo | oil on canvas | 110x125x2cm | 1987 | Private Collection

Alentejo | oil on canvas | 70x90x2cm | 1988

Ribatejo | oil on canvas | 90x110x2cm | 1987 | Private Collection

Alentejo | oil on canvas | 110x125x2cm | 1988 | Private Collection

Ribatejo | oil on canvas | 90x100x2cm | 1987 | Private Collection

Minho | oil on canvas | 90x100x2cm | 1987 | Private Collection

Ribatejo | oil on canvas | 90x120x2cm | 1989 | Private Collection

Landscape | oil on canvas | 90x100x2cm | 1989 | Private Collection

Ribatejo | oil on canvas | 85x110x2cm | 1989 | Private Collection

Alentejo | oil on canvas | 110x125x2cm | 1989 | Private Collection

Encounter with the Nature

The landscape is a pictorial genre that always occupied a secondary place, being subalternized by the academic hierarchy until the XVIII century. During the middle ages and renaissance periods, the landscape emerges as a background of artistic representations, divine or mythological, and never as a main artwork.

Giotto, in the XIV century, by bringing perspective to the painting, introduced tri-dimensional space, leaving behind a flat background, most of the times golden, from the byzantine period on which were painted sacred representations. However, even regarding Giotto, the relevance was always given to the divine figurative form, appearing the landscape as a background or a subordinated and supplementary space, showing minor details, presented as a tree, a little sky, or a rock, almost always painted by his helpers.

Only during the XVII century, the academy would consider the landscape as a genre painting, even though, located in a space of little relevance, relayed to the function of background to the historical paintings, portraits paintings, or others.

It was in Holland that it acquired his status of landscape painting and affirmed itself as an artistic specialization, being then defined as the art that represents nature scenery. The protestant reform, the development of collectionism habits, with the appearance of a bourgeois society composed by rich merchants, came to substitute the clergy and nobility’s preference of sacred themes, classical antiquity and mythology, by the quotidian themes, less complex like landscapes or genre scenes. Therefore, the landscape acquired status and iconographic autonomy, constituting itself as an autonomous genre, which gained legitimacy through the works of some Dutch painters that assumed it as a main motivation, bringing to the canvas nature scenery, with polders, windmills, canals, pathways populated by trees, forests and other representations. In this genre, we can mention, Meindert Hobbema, Salomon van Ruysdael, and Jan van Goyen, as the great pioneers.

It is, finally, with the arrival of the last decades of de XIX century and principally with the Impressionism and the Post-Impressionism, that the legitimate importance will be attributed to landscape, importance that was always denied, until then. The artist, willing to paint his landscapes, went to inhabit the nature, working in the middle of the nature and depending on the nature to achieve his artworks. And in the middle of the nature was the landscape. Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissaro and Van Gogh, among others, were painters that contributed, significantly, to put the landscape genre in a high ranked position in the art history.

In the XX century, modern art, at its peak, attributed to it very little relevance; the post-modern art even less.

Pintomeira initiated his artistic activity in the post-modern time, not having, for this reason, any connection or influence coming from the landscape. He never was a landscape painter, he never let himself being sensibilized to the aesthetical expression brought by the genre in question. It is understandable that, Pintomeira, having been a surrealist, never had been aroused or enchanted by one artistic expression which goes along side by side with reality, pretending to imitate nature. In his generation, the landscape genre wasn’t, far from it, a vanguard, even though some Hyper-realists painted it. Back then, the landscape was (dis)consider a musty thing or a hobby of the so called “Sunday painters”. The museum rooms and prestigious galleries didn’t recognize it as a vanguard and did not exhibited it. On the other side, rarely, a famous contemporary artists painted it or gave it any attention. Lately, David Hockney and April Gornik showed to us some impressive landscapes.

Analysing all his journey until today, we can conclude that Pintomeira never followed tendencies nor left himself become entangled by galleries preferences, rejecting the established art market and its demands that most of the time strangled the artist’s creative freedom.

And, master of his own freedom, he decided to have an encounter with the nature. We wrote, above, that the landscape never thrilled him and that he never was a landscape painter. And we wrote the truth. But, as a nature lover he felt himself compelled to bring the landscape to his atelier, to painting it and putting it on canvas. And that would happen. Based on some photographs, obtained by him, of the Alentejo plains, in one of the trips he made to his country, Portugal, Pintomeira started, in his atelier in Amsterdam, an experience around the landscape that would result in the creation of thirty works. All of them belonging today to collections in diverse countries, except one that the artist made a point to keep, with the intention to remembering him an unplanned experience that, fortuitously, happened in his atelier, having stayed there for three years, during the eighties.

I think that, after a more attentive observation of his photographs, he defined the conceptual language that best fitted to an original and innovative representation. Pintomeira opted to make a structural analysis of the Alentejo plains and concluded that his work would be rather more one of rational construction than one influenced by emotional feelings. It wasn’t his idea to mimic nature nor being touched by its intrinsic beauty or by its bucolicism, excluding any approach to the Arcadianism.

The option for a rational construct of the aesthetical expression would be based, ab initio, on the vast space-air that the plain’s image would offer to him. Even though, not respecting any academic rule of perspective, the representation of this vast space, this enormous portion of atmosphere, would be brought by the strong illusion of depth expressed through a shape construction depicted in traces, lines, rectangles and other geometrical shapes and in a chromatic construct bringing the warm colours to the proximity and placing the cold and undefined tones to the horizon, producing an appearance of faraway: Alentejo 7. Inside the aesthetical and formal pre-established conception, the composition presents itself as minimalist, without the elements that, normally, compose a landscape: trees, rivers, people, animals, etc. This was the main line with which he structured most of his works, existing a few where we can see some elements such as some tree trunks, meaning geometric lines, but never eliminating the concept that was formerly determined: the strong apprehension of space and depth.

Pintomeira realized his meeting with the nature, offering to us this artistic expression about the landscape genre that, having never been his artistic expression area, far from it, he considered an inevitability bringing it to his atelier, where he worked it, following his own signature and aesthetical conception.